Ken Caminiti's favorite sport to play wasn't baseball. It was football.

“I used to think he was like a ram. One of those rams on the mountainside that would just duck its head and hit you as hard as possible.”

Elements of this essay appear in my book Playing Through the Pain: Ken Caminiti and the Steroids Confession That Changed Baseball Forever.

Football was the perfect sport for Kenny Caminiti.1 He could run and jump and catch and smash into things.

Smashing into things was his favorite.

“He would try to disassemble your body,” high school teammate Victor Armstead said.

For Tim Cogil, “I used to think he was like a ram. One of those rams on the mountainside that would just duck its head and hit you as hard as possible.”

These were teammates comparing him to a battering ram. Just think of what he did to the guys on the other teams…

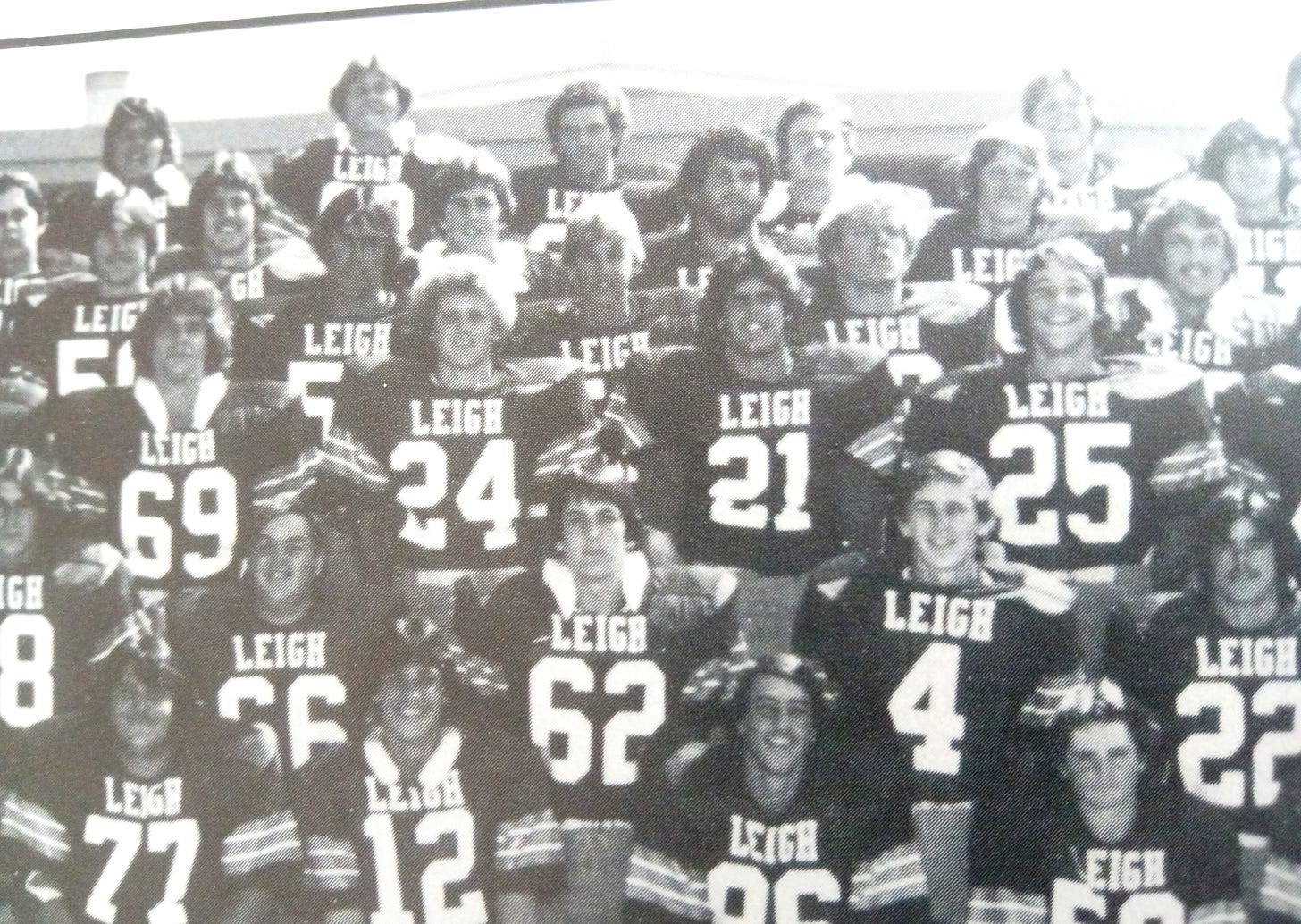

… And yet, the San Jose, California-based Leigh High was never much more than a .500 team with its battering ram on the field. Win against Lincoln, loss against Branham, win against Delmar, loss against Westmont.

Come to think of it, none of Kenny’s high school teams were very good. Kenny was one of the best players, if not the best, on whatever field he stepped on. His teammates and opponents knew he was special — no one could have predicted exactly how far he’d go in sports, but you couldn’t help but watch him. He was bound to impress you somehow.

Football brought out Kenny’s ingenuity and athleticism. He could impact a game so many ways. Blocking, eluding a tackle, making a hit, hauling in a catch, running the ball, making an interception.

WATCH: Ken Caminiti high school football game video

Kenny typically played wideout on offense and defensive back on defense. While opposing quarterbacks learned not to throw his way — he was liable to pick off a pass or deliver bruising hits on receivers — his own run-first offense didn’t throw the ball his way enough, either.

“If you wanted three yards and a cloud of dust football, Coach Holland was the right guy for that,” Kenny’s teammate and friend Chris Camilli said.

Kenny always had the best hands on the team. Vito Cangemi, Leigh’s kicker, who’d go on to participate in four NFL training camps and become a longtime high school coach, felt especially comfortable with his holder on extra points, a sure-handed teammate, someone he trusted — Kenny.

“He was our best receiver on our team, but he could've played quarterback too because he had such a good arm,” Cangemi said. “Whatever he did, he was the kind of guy that you could teach him how to do something and he'd beat you at it the first time. That was his natural ability, his talent. It was in his makeup, his DNA.”

Kenny got to show off all of his skills in a September 1980 game against Harbor High during his senior year. He lined up at halfback, took the pitch and ran right — the play was “48 sweep pass” — but instead of running upfield, Ken stayed behind the line of scrimmage and looked for a receiver.

Teammate Mike Griffin was open along the sideline, so Ken “rared back and hurled a bomb … Griffin waltzed into the endzone untouched for Leigh’s third TD of the game,” according to the Santa Cruz Sentinel. Kenny added eight rushes for 41 yards, including a 14-yard touchdown, in the 35-13 Longhorns win.

But all the battering ram effort took its toll — he jammed his neck his senior football season.

“We had a policy that you had to practice in order to play, and he got his neck jacked up and had to sit out and he's wanting to practice,” high school football teammate Mark Beltramo said. “And the coach was like, ‘no, Kenny, you go sit out. I'll get you a lawn chair.’ ‘Yeah, but I want to play.’ ‘Don't worry, you're gonna play.’”

On the football field, Kenny was always dealing with bumps and bruises. He tried to keep quiet about them, doing whatever he could to stay on the field. Sometimes he’d grit it out. What’s a little pain? Or he’d use a splint and tape. His brother Glenn, who was two years older, would help him conceal his injuries.

Some of those bumps and bruises would linger into Ken’s pro baseball days.

“His shoulder problems started from playing football,” Cangemi said. “It was a football injury that he had his junior and senior year.”

At the end of his senior year, he was selected for a county all-star football game along with teammate Nick Neri. The best players of the South Bay against top players from the North Bay.

Santa Teresa High’s Craig Fontaine, like Kenny a defensive back, was impressed by Kenny’s athletic talent: who is this white guy who can cover anybody, leap out of his shoes, and hit you like a freight train? Fontane got his formal introduction to Kenny during a practice at Gavilan College when they were participating in a defensive back drill.

“Kenny and I were going back for the ball, and we're both going flat out, and I remember jumping for the ball and something hit me in the side of the helmet ... And then I was in the locker room, and it was Ken that clobbered me,” Fontaine said.

With the help of Kenny’s standout defense, his team, South, won the game 5-0 in front of about 5,000 fans at San Jose State University's Spartan Stadium.

Given Kenny’s football injuries, playing his favorite sport in college wasn’t in the cards. But there was always baseball. He would carry his football mentality onto the diamond — still running and jumping and catching, and still smashing into things.

While he was best known to baseball fans as Ken, Caminiti went by "Kenny” in his younger days. I’ve used those names interchangeably throughout this essay.