Aces wild

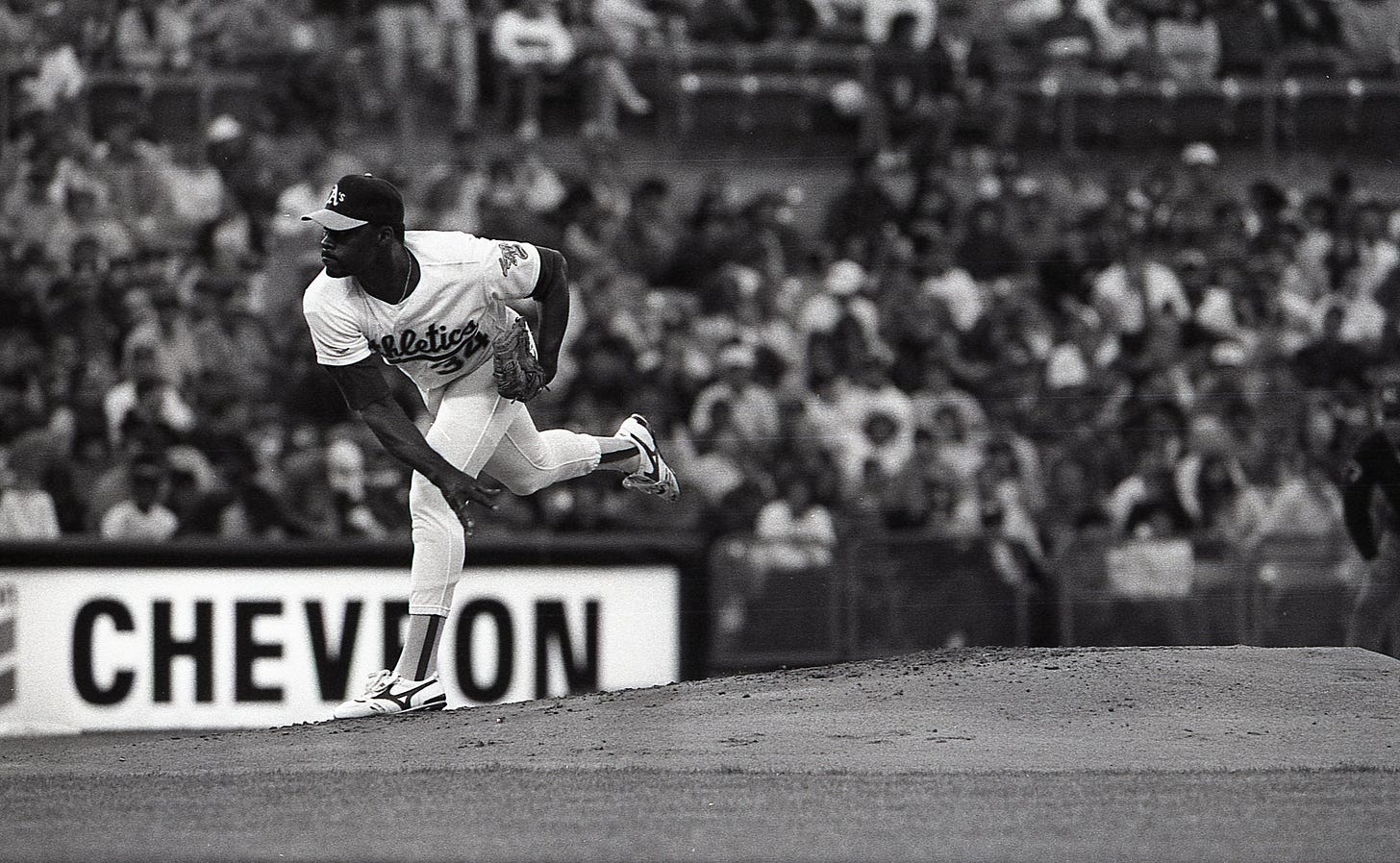

Padres pitching coach Dave Stewart helped to instill intensity in San Diego’s pitching staff in 1998. It didn't hurt having Kevin Brown and Trevor Hoffman in the mix.

With the Padres advancing the NLCS for the first time in 24 years, I’m taking a look back at the 1998 team. The following text is adapted from my book Playing Through the Pain: Ken Caminiti and the Steroids Confession That Changed Baseball Forever.

The Padres were ready to roll the dice.

Despite a first-to-worst turn in 1997, San Diego featured the core of a winning ball club. The outfield, with Tony Gwynn in right, Steve Finley in center, and Greg Vaughn in left, had the potential to generate lots of runs. Corner infielders Ken Caminiti and Wally Joyner could carry the team and provided veteran leadership. Quilvio Veras and Chris Gomez were steady at second and short, and Carlos Hernández had pop in his bat at catcher. Closer Trevor Hoffman anchored San Diego’s bullpen. Hoffman would enter games to the AC/DC song “Hells Bells,” and from the first guitar chords to the final out, everything was electric.

But the rotation was missing something.

An edge.

The kind of intensity Dave Stewart possessed during his playing days.

He was a guy you didn’t mess with, someone who owned the mound, and the plate, and your mind. After Padres pitching coach Dan Warthen was fired at the end of the 1997 season, GM Kevin Towers decided to fill the role from within the front office—Stewart was already serving as a special assistant for the Padres, and now he’d pick up coaching duties, too.

Stewart’s task: Make the Padres pitchers own the games they started. Make every pitch count. And make the opposition fear you. Improve on the previous year’s 47–62 record, 4.98 ERA, and 933 innings pitched, or about 5.75 per start.

He set the intensity level from the first day of spring training, making sure the pitchers did extra running. They needed to be better conditioned. That would cut down on the injuries and help them go deeper in games.

“They were a good group of guys that were anxious to learn, and they were also anxious to compete,” Stewart said.

It helped having a true ace, a number one starter, someone who could go toe to toe with the other team’s best pitcher. Someone who could neutralize a Maddux or Smoltz or Martínez or Johnson or Mussina. The Marlins happened to have just that kind of ace in Kevin Brown and were in a liquidation sale, just like your local furniture store—everything must go—after winning a surprise World Series. The thirty-two-year-old Brown went 16–8 during the 1997 season, then outdueled “Mad Dog” Maddux and “Gretzky” Glavine in the playoffs with ice in his veins.

The Marlins fielded offers for Brown, who had one year left on his contract. The Mets were a possible destination, but San Diego offered three prospects (one of whom was Derrek Lee, a first baseman who went on to have a solid career).

Having Brown allowed the Padres to move Andy Ashby and Joey Hamilton and Sterling Hitchcock back in the rotation. Between Brown and Stewart, the Padres had a new tone and depth and mandate: Win now.

Brown, a ground ball pitcher who started tinkering with a forkball that spring, would compile an 18-7 record with a 2.38 ERA in 1998 and a WHIP of 1.180.

He led the majors that year in Wins Above Replacement—finishing ahead of Mark McGwire, ahead of Sammy Sosa, ahead of Barry Bonds, ahead of everybody.

And he was the perfect ace for a team destined for October.

The other pitchers followed suit, putting together career seasons of their own. Ashby was 17-9 with a 3.34 ERA.

Hamilton won 13 games.

Hitchcock bounced between the bullpen and rotation earlier in the year before settling into a groove.

The middle relief was led by Brian Boehringer (5-2, 4.36 ERA in 56 games), Dan Miceli (10-5, 3.22 ERA in 67 games) and Donne Wall (5-4, 2.43 ERA in 46 games).

And then there was Hoffman, the fireman, to finish it off.

A converted shortstop, Hoffman had been acquired from the expansion Florida Marlins when San Diego traded away Gary Sheffield in 1993. He was becoming dominant with the help of his changeup after fellow reliever Donnie Elliott taught him a new way to grip the ball in 1994.

He was never better than 1998, when he saved 53 games with a 1.48 earned run average.

Hoffman and Brown finished second and third, respectively, in Cy Young voting.

The strong outings and sharp relief work effectively shortened games. It streamlined the path to Hoffman and left opponents gasping. Stewart’s intensity had worn off on his staff.