You're thinking about steroids in baseball all wrong

PEDs have been in baseball far longer, and the problem goes much deeper, than most fans realize.

The witch hunt continues anew, as it does every January, as it will whenever a 1990s-era baseball player is up for Hall of Fame consideration, or a coaching job, or debate on social media.

Players of the 1990s and early 2000s have faced waves of backlash for what they put into their bodies, and I don't think the fervor is fair. Especially when PEDs have been in baseball far longer, and the problem goes much deeper, than most fans realize.

Performance-enhancing drugs have been a part of professional baseball since at least the ’80s — the 1880s, that is. It all started with juice from crushed dog and guinea pig testicles.

James “Pud” Galvin, baseball’s first three-hundred-game winner, received injections of a substance obtained from animal testicles, a process known as Brown-Séquard Elixir, in 1889. One day after receiving his injection, Galvin took the mound for the Pittsburgh Alleghenys and guided the team to a 9–0 win against the Boston Beaneaters.

But instead of being vilified, Galvin was adored for taking such extreme measures.

“If there still be doubting Thomases who concede no virtue of the elixir, they are respectfully referred to Galvin’s record in yesterday’s Boston-Pittsburgh game. It is the best proof yet furnished of the value of the discovery,” the Washington Post wrote in 1889.

The elixir, as it turns out, was literal and figurative junk science — it didn’t work. But either way, Galvin, baseball’s first known PED user, entered the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1965. His plaque hangs in Cooperstown next to the one honoring Red Sox slugger Ted Williams.

Players have used various performance enhancers throughout the 1900s, mainly amphetamines known by an assortment of colorful names — pep pills, uppers, red juice, and greenies — pick-me-ups to endure the bumps and bruises and travel and pounding of playing 150-odd games across six months.

Stimulants were everywhere in the game. Some teams supplied them to players.

Scientific possibilities exploded with the synthesis of anabolic-androgenic steroids during the 1930s (anabolic means “muscle building,” while androgenic means “male”). The drugs offered the promise of increased masculinity and strength, youth and vigor, in pill or injectable form.

By the late 1960s and early 1970s, anabolics had made their way to baseball, with a handful of users estimated on each team.

"We were doing steroids they wouldn't give to horses. That was the '60s, when nobody knew. The good thing is, we know now. There's a lot more research and understanding," pitcher Tom House told the San Francisco Chronicle in a 2005 interview.

Nolan Ryan, meanwhile, has said that he recognized steroids infiltrating the game by the late 1970s.

The game was initially reluctant to embrace muscle and weight lifting. Muscle-bound players were thought to break down easier and be less nimble. And some of the game’s greatest home run hitters, such as Hank Aaron and Willie Mays, were lithe and lean.

By the 1980s, the underground steroid culture full of pills and needles and powders trickled further and further into baseball. One of baseball’s earlier admitted users of anabolic steroids, outfielder Glenn Wilson, said he acquired drugs from a friend during the 1984 off-season and spent that winter lifting heavily. The drugs appear to have worked for Wilson — he put up his best offensive numbers the season after using steroids, stroking 24 home runs and driving in 99 runs, and made his only All-Star team.

Wilson said that beyond the physical boost, steroids gave him newfound confidence in the batter’s box.

“Before steroids and I face Nolan Ryan, I’m shaking in my shoes. After taking steroids, facing Nolan Ryan is like facing my son throwing batting practice,” Wilson told me in a 2013 interview.

Phil Garner, a second and third baseman during the 1970s and 1980s affectionately nicknamed “Scrap Iron” for his relentlessness and grit, faced his own crossroads after undergoing back surgery in 1988 as his career wound down. He researched steroids to see if they could help him get back on the field.

“In the end, I decided not to do it, not for any high and mighty, moral reason,” Garner said. “I didn’t think it would be good health-wise later in life.”

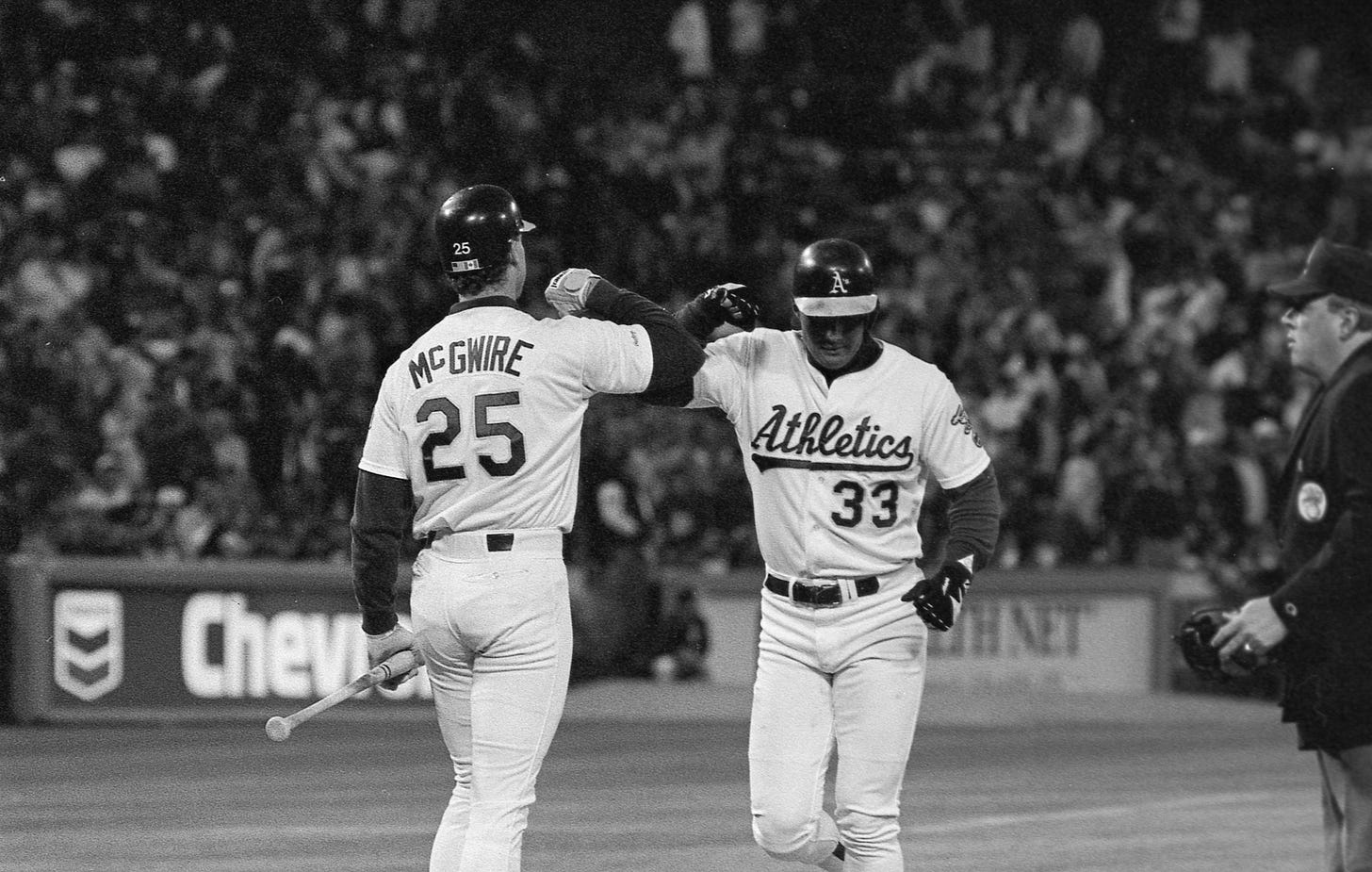

One team, the Oakland Athletics led by sluggers Mark McGwire and José Canseco, became the face … er, biceps of baseball’s changing physique. Canseco in 1988 became the first player to hit 40 home runs and steal 40 bases in a season. Canseco, meanwhile, set a rookie record with 49 homers in 1987.

The "Bash Brothers" pounded their forearms together after home runs, a ritualistic display of masculinity. They were exciting and fun, Adonises in green stirrups. They were also juicing, and it wasn’t a well-kept secret, especially where Canseco was concerned.

As the 1988 season wound down, the Washington Post columnist Tom Boswell, appearing on the CBS program Newswatch, called Canseco “the most conspicuous example of a player who has made himself great with steroids.”

When Red Sox fans taunted Canseco, chanting Ster-oids! Ster-oids!, he smirked and flexed his biceps to the crowd. The month after Canseco’s playful muscle flex, Congress passed the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1988, the first significant federal regulation of steroids. Two years later, the Anabolic Steroid Enforcement Act of 1990 made some anabolic steroids Schedule III controlled substances, denoting certain health benefits and less potential for abuse than street drugs such as cocaine but the potential for physical and psychological dependence.

As the Bash Brothers were mashing in the late 1980s, baseball already had a steroids problem on its hands, Dr. Charles Yesalis, one of the country's leading experts on performance-enhancing drugs, has said.

Major League Baseball finally did something about steroids in 1991: It added the drugs to its banned substance list. Commissioner Fay Vincent wrote a memo that mentioned steroids: “Illegal drug use can cause injuries on the field, diminished job performance and alienation of those on whom the game’s success depends -- baseball fans. Baseball players and personnel cannot be permitted to give even the slightest suggestion that illegal drug use is either acceptable or safe. It is the responsibility of all Baseball players and personnel to see that the use of illegal drugs does not occur, or if it does to put a stop to it by the most effective means possible.”

That was it. There was no testing, penalties, or rehabilitation for players who used them.

Drug testing would need to be approved by the players’ union. MLB’s memo amounted to self-righteous finger-wagging — a bunch of toothless, empty words.

By that point, federal investigators were cracking down on a steroid distribution ring that ensnared several players, including the “Bash Brothers,” Canseco and McGwire. But because the players were buyers and not suppliers, the FBI didn’t expose them, deciding instead to alert Major League Baseball.

MLB, when confronted with information about their players using steroids, did nothing. Steroid testing was briefly considered by the owners but not pursued -- as MLB and the Major League Baseball Players Association negotiated before the 1994 player strike.

“We tried to warn ’em,” said retired FBI agent Greg Stejskal, the lead investigator of the steroid probe called “Operation Equine.” Stejskal alerted a senior MLB official in August 1994 about PED use in baseball. The response: “We kind of know about it, but there’s not really much we can do because the players won’t let us test,” Stejskal said.

Players who used steroids had no reason to stop.

And then the 1994 player strike happened.

The strike meant MLB players, from August 1994 until March 1995, couldn't work out at major league facilities with major league coaches and staff.

Players had to work out on their own. They'd train with fellow players or friends who had some training experience, sharing insight and tips.

The strike made players — especially stars — less reliant on their teams, and more reliant on their own connections and personnel.

Salaries were rising rapidly, and players were taking better care of themselves.

And by the mid-1990s, the supplement creatine, an enzyme found in red meat and seafood that produced results similar to those of anabolics, had become all the rage, muddying the line between legal and illegal and offering the perfect cover as players used steroids to grow bigger and bigger.

I remember when I was playing high school football at Manheim Township in Lancaster, Pa., from 1998 to 2000.

I hit the weight room hard my sophomore and junior years. I was making small gains and steady progress, upping my weights five pounds a week, but other teammates -- some who were taking creatine and god knows what else -- were far surpassing me, repping 225 on bench when I was struggling to max out at 175. I wasn't adding enough muscle to become the player I wanted to be. I was also 5'7" at the time, and still filling out (I'd grow five inches my senior year).

I never gave creatine or other performance-enhancing substances, legal or otherwise, much thought. There was a stigma there, and the unknowns of the long-term effects, but ultimately I didn't have a strong feeling about it one way or another. Football wasn't my life, which is why I eventually quit to focus on journalism.

But what if football was my life?

And what if I needed to keep pace with other players?

And what if it was my means of supporting myself and my family, and my career would all be wiped away if I didn't add more muscle or bounce back quickly from an injury?

I think about that sometimes when I consider what I would have done if I were a major leaguer during the 1990s and early 2000s. It's easy enough to suggest you would have a strong enough moral code to be able to say no. Some players did! Players such as Frank Thomas, Rick Helling and Brian Johnson took a hard line against PEDs. Kudos to them.

Doug Glanville wrote eloquently about this for ESPN, and if you haven’t read his column, please do so.

The lines you draw are different when you are directly impacted by such rampant cheating. Not peripherally, not theoretically, but directly -- in your contract negotiations, on the lineup card, on the depth chart, in the win column.

It is one thing to watch artificial domination on TV, marveling at the numbers it produced as if it is a magic show. It is another when you lose your job from it.

Here’s another paragraph of Glanville’s that was especially poignant.

It's not just Bonds. So many players from the steroid era -- the era of my own professional career -- bulldozed everyone else to pad their stats. Apologists couch it in competitive spirit or a relentless will to win, but in the end it was just egomaniacal avarice, unleashed to compensate for the same insecurity that every major league player feels.

For the players who chose to use PEDs, I understand. For those who didn’t use PEDs, I feel for you — you faced an impossible task.

Bob Gibson was among the most respected competitors in baseball history.

The Cardinals pitching legend had a meaningful response when asked about steroids during a 2013 interview.

"Oh, I don't know that it's really tainted the game. If you probably go back and check, guys have been cheating ever since baseball's been baseball, one way or another. You talk about the, what was that, the old White Sox scandal or whatever it was? The guys have just been cheating and throw spitballs, and if you can get an edge, you get an edge. Now this is something that was unacceptable as far as our society is concerned, so, you know, it got so much press, that it got probably bigger than it should have been. It's something that's illegal as far as our country is concerned, and I think that's probably the biggest problem, but I'm just glad that I didn't have to make that decision on whether to do it or not, because I'd been one of those guys you write about. Probably would've done it, I don't know. I'd like to think I wouldn't have, but I don't know if I'm that strong. If I thought somebody was getting the edge on me and I found a way that I could get it back, maybe I would. Don't know. I'm glad I didn't have to make that decision."

Phillies hall of fame third baseman Mike Schmidt has made similar comments, speculating in 2005 that he would have strongly considered taking steroids if he played a decade later.

Trying to quantify the percentage of 1990s baseball players who used steroids is a fool's errand.

Los Angeles Times sportswriter Bob Nightengale wrote an article about steroids in 1995 in which Padres GM Randy Smith estimated that 10 to 20 percent of players were using steroids. An unnamed American League GM told Nightengale, "I wouldn’t be surprised if it’s closer to 30 percent, although most people will say it’s about 5 percent to 10 percent. We had one team in our league a few years ago that the entire lineup may have been on it."

Pitcher Jack Armstrong guessed that 20 to 30 percent of players were juicing heavily during his career, which lasted from 1988 to 1994.

The late, great Tony Gwynn has estimated 20 percent.

Jose Canseco, hyping a book that would come out years later, told Jim Rome in May 2002 that 85 percent of players were using. It was quickly brushed aside. Eighty-five?

Ken Caminiti, in bravely coming forward to discuss his own use of steroids to Sports Illustrated the same month, was vilified for guessing that half of players were juicing. In that article, Chad Curtis estimated that 40 to 50 percent of players were using.

The following year, 2003, 7 percent of MLB players failed drug tests — a number that doesn’t take into account players who took undetectable steroids such as hGH, or those who cycled off steroids ahead of their test, or those who started using again after getting tested.

If 7 percent is too low a number, and 85 percent is too high, then the actual number has to be somewhere in between those two extremes, no? The number directly in the middle between 7 and 85 is ... 46. Which is in line with Caminiti's rough estimate.

There's no way of knowing the true number. But Ken had some context and insight into players' use of PEDs. Which is why I think his guess hit the hardest across the league.

"I remember when he first came out with that percentage of guys using. I was like, there's no way that percentage could be that high," said Cardinals catcher Tom Pagnozzi, a friend of Ken's who played winter ball with him in the late 1980s. In Pagnozzi's mind, pitchers couldn't be juicing the way position players were. But when looking at the players who've tested positive and been suspended, many have been pitchers.

"Because he was using it, he knew who was using it. He was right on, and people just wanted to disregard what he was saying," Pagnozzi said of Ken's steroids admission.

Tom Verducci, the author of the landmark 2002 SI article, said fans continue to be hung up on the percentage of users.

"People ask me all the time, what percentage of players were using? I don't know, it was a lot. If you say it's 30 percent or it's 40 percent or it's 60 percent, then people fixate on the number," Verducci told me in 2020 "I think he just threw out an estimation, not trying to be specific in any shape or form, and people just kind of hung onto that. Ooh, half the players. And that just resonated with so many people.

"These obviously are not scientific figures, but the public ... seems to fixate on a very firm number as a percentage. Whether it was 50 percent or 40 percent or 25 percent, to me, it really didn't matter. What he was saying was, this is rampant, there's a lot going on."

The steroids conversation has mainly centered on the players who benefitted most from the drugs, like Caminiti, who won the MVP award, or Bonds, who shattered the single-season and career home run records, or Clemens, who rewrote the modern pitching record book.

But what about those players who didn't benefit from taking steroids? Or those whose use went under the radar? For every Bonds or Caminiti there were scrub middle infielders whose bloop singles turned into lazy flyouts, or journeyman relievers bouncing back from surgery, or faded prospects trying to salvage their careers, or fourth outfielders hoping to make a team out of spring training, or emerging stars who got too muscle-bound and too injury-prone.

Even on steroids, you still need to hit the ball or make your pitches. Lots of players took steroids and still couldn’t deliver.

And focusing on Bonds or Clemens in a vacuum fails to account for all the home runs that Bonds slugged off of juicing pitchers, or Clemens' strikeout victims that were using themselves.

Something important happened on August 23, 1998, but everyone was too busy paying attention to something else.

That day, in a half-empty ballpark, with little fanfare, Barry Bonds smashed his 400th career home run, making him the first player in baseball history to hit 400 dingers and steal 400 bases. Only three players had achieved 300-300: Joe DiMaggio, Willie Mays, and Barry's father Bobby.

It was a massive accomplishment. But everyone was focused on Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa’s home run chase that summer.

"This is nothing," Bonds said after the game. "I've got nine writers standing here. McGwire had 200 writers when he had 30 home runs.

"What they're going through is huge. You have two players who might break the record in the same year. That's crazy!"

The off-season after Bonds was overlooked at reaching 400-400, according to the book Game of Shadows and other reporting, was when he decided to begin using PEDs. He was angry and bitter about all of the media and fan hype and adoration for McGwire.

And why wouldn't he be?

Now, 20-plus years later, media and fans are still trying to pin the blame on players like Bonds and McGwire and Clemens, failing to recognize the scope of the problem or their own role in the myth-making and hero worship that fueled a now-tarnished era.