The Astros were almost the dynasty of the 1990s. Then they traded away Lofton and Schilling.

"We felt like we had a great nucleus of guys, and the team just kind of got separated, torn apart," Luis Gonzalez said.

The losses piled up.

The Astros were the laughingstock of the league.

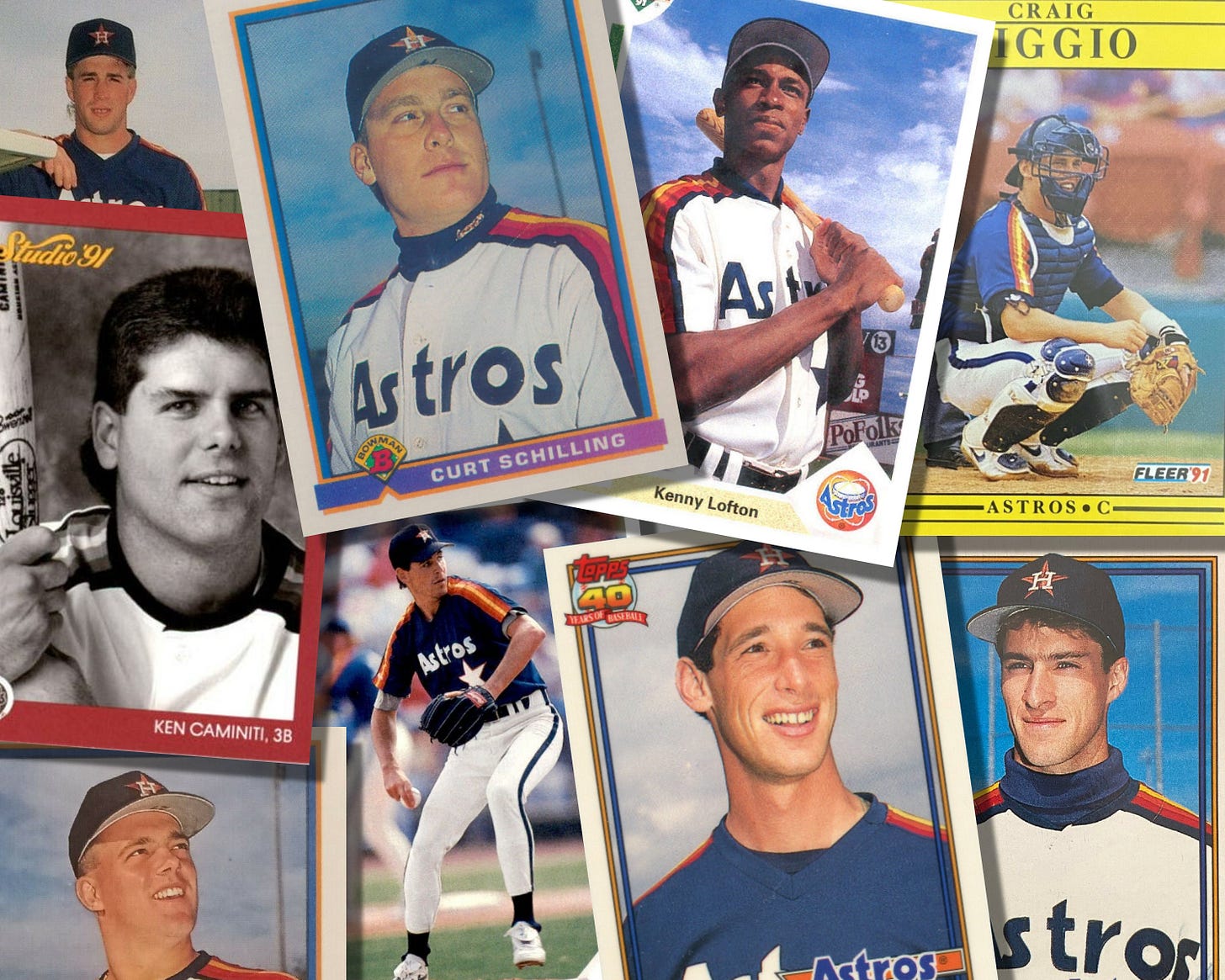

It was impossible to know at the time, but something special was brewing. Behind a scrawny second baseman, a scrappy third baseman with power, an up-and-coming star who always seemed to hit a home run when it mattered most, a sparkplug outfielder, and an ace who saved his best for October, the moribund franchise became a dynasty in the making.

No, I'm not referring to the 2014-16 Astros, when a core of Altuve-Bregman-Correa-Springer-Keuchel helped bring a championship to H-town. Before them came the 1991 Astros, another band of young players who endured lots of losses on their way to becoming stars:

Craig Biggio, an All-Star catcher who planned to move to second base to prolong his career

Jeff Bagwell, on his way to being named Rookie of the Year

Kenny Lofton, the former University of Arizona basketball player turned fleet-footed centerfielder

Curt Schilling, a hard-headed pitcher with ace potential

Ken Caminiti, one of the top-fielding third basemen in the league and a switch-hitter with pop

Steve Finley, a Gold Glove-caliber outfielder

Luis Gonzalez, an emerging left fielder with a sweet swing

Darryl Kile, an Astros prospect with no-hit stuff, including a dominant curveball

Pete Harnisch, among the National League leaders in Earned Run Average in 1991 and an All-Star selection

All of these players were teammates together in September 1991 on a 97-loss Astros team. And to top it off, Houston owned the rights to the top pick in the 1992 draft.

This team was poised to become the dynasty of the 1990s, even beyond Atlanta or the Yankees.

If only Houston had kept the players together...

"We felt like we had a great nucleus of guys, and the team just kind of got separated, torn apart," Luis Gonzalez told me in a 2015 interview. "Everybody went on to go ahead and become decent ballplayers. It would've been great to see what this team would have been able to do if we would've stuck together five or 10 years, because we felt like we were moving in the right direction."

Houston's roster turns over

After a thrilling NLCS against the Mets in 1986 and lackluster finishes in 1987 and 1988, the aging Astros started turning over its roster. Veteran players were sent packing, one after another, a means for owner John McMullen to save money.

Houston offered a lowball offer to pitcher Nolan Ryan, the team’s local legend, only to see him leave for the cross-state Rangers to become an institution, the Ryan Express.

Kevin Bass and Bob Knepper went to the Giants.

Craig Reynolds retired. Alan Ashby was released. Terry Puhl became a free agent and washed up with the Mets and Royals. Billy Doran was traded to the Reds, the eventual World Series champions.

The departures opened up opportunities for Houston prospects like Caminiti, Biggio, Gerald Young, Eric Yelding and Eric Anthony (some of the prospects worked out better than others). Other Houston farmhands like Luis Gonzalez and Kenny Lofton (both drafted in 1988) were waiting in the wings.

The youth movement was starting to take shape.

But things really took off because of two massively lopsided trades.

The first happened because Boston was desperate for relief help during its 1990 playoff run -- so much so, that it gave up third base prospect Jeff Bagwell to acquire reliever Larry Andersen (Bagwell's path to the majors was blocked by Wade Boggs). Andersen ended up pitching 22 innings in the regular season for the Red Sox, and after a sweep in the ALCS, he was a free agent.

The second trade came in January 1991, because Houston's slugging first baseman Glenn Davis wanted to get paid — he was facing arbitration with free-agency looming, and there was no way Houston was going to pay him, so instead they shipped Davis off to Baltimore, and in return, Houston got a haul of young players: outfielder Steve Finley, starting pitcher Pete Harnisch, and relief pitcher Curt Schilling. It was a steep cost for the Orioles — you never know what will come from trading prospects. Sometimes they fade out. And sometimes they become All-Stars and World Series heroes, and you kick yourself for giving them away before they could do it for your team.

At the time, it appeared that Baltimore had gotten the better of the deal. How was anyone to know that Davis would only hit 24 home runs across three injury-plagued seasons for the Orioles? Or that Finley, Schilling and Harnisch would have such successful careers ahead of them?

The young Astros didn’t win very often in 1991. But they had fight.

Within a year, the Astros were back to being a .500 team — a 16-win turnaround.

"We were very, very young. You just knew you were going to take lumps," Art Howe, the Astros manager from 1989 to 1993, told me. "But very quickly, you could see them starting to get their feet on the ground and start to give the lumps back. And that's what's fun about when you do rebuild and you get the right people in place, the right players, it's just a matter of time until the tide turns. And it's really fun to be a part of that."

Measuring Future WAR

It's difficult to quantify a team's "Future WAR," the Wins Above Replacement a group of players will compile after a certain point. Stathead doesn't have the stat readily available or easily measurable (I asked), but looking at the 1991 Astros, it becomes clear that this was the start of something big. Something unique. Something historic.

Schilling — career WAR: 80.5 (0.2 through 1991) = 80.3 remaining WAR

Bagwell — career WAR: 79.9 (4.8 in 1991) = 75.1 remaining WAR

Lofton — career WAR: 68.3 (0.0 in 1991) = 68.3 remaining WAR

Biggio — career WAR: 65.5 (10.3 through 1991) = 55.2 remaining WAR

Gonzalez — career WAR: 51.8 (3.6 through 1991) = 48.2 remaining WAR

Finley — career WAR: 44.3 (5.9 through 1991) = 38.4 remaining WAR

Caminiti — career WAR: 33.5 (6 WAR through 1991) = 27.5 remaining WAR

Kile — career WAR: 20.6 (-.3 through 1991) = 20.9 remaining WAR

Harnisch — career WAR: 19 (5.9 through 1991) = 13.1 remaining WAR

Those players would compile 427 WAR during the remainder of their careers. Which is a higher total Future WAR than at any specific point in time for the most dominant teams of the 1990s.

At the end of the 1993 season, Atlanta's core roster had 378.2 remaining WAR, including Chipper Jones (85.1), Greg Maddux (72.6), Tom Glavine (54.9) and John Smoltz (48.1).

The Yankees of the mid-1990s also had a young core of talent, and at the start of the 1996 season, the team's key players, led by Derek Jeter (71.6), Andy Pettitte (57.7), Jorge Posada (42.7) and Bernie Williams (35.1), had many successful years ahead, and 358.4 Future WAR.

The 1990 Mariners opened the season with Ken Griffey Jr. (80.6), Randy Johnson (103.4) and Edgar Martinez (67.7) all near the start of their Hall of Fame careers, along with Omar Vizquel (44.9) and Tino Martinez (29), but the roster was also intermixed with veterans.

Many rebuilding teams have key players join over the course of numerous seasons or a roster that gradually replenishes. Other teams turn to a youth movement with players who turn out to be pretty mediocre. It's hard to find a team quite like the 1991 Houston Astros, when so many good players were simultaneously at the start of their careers. Even teams that committed to a youth movement or made a good draft run (such as the Athletics and Dodgers of the 1960s, late 1970s Tigers, or the Cubs or A’s of the mid-1980s) didn't have such high measurements of Future WAR at one moment.

One team that does match up -- I'm sure there are a few others from the early 1900s -- is the 1954 Milwaukee Braves, Hank Aaron's debut season. Aaron compiled 143.1 WAR during his career, and many of his teammates had long successful careers ahead of them, including Eddie Matthews (85.6 Future WAR) Warren Spahn (43.7), Joe Adcock (29.5), Johnny Logan (26.5), Del Crandell (26.2), Bill Bruton (25.6), Bob Buhl (24.8), Lew Burdette (19.6), Gene Conley (16.3) and Danny O'Connell (13.2). That group -- in a much smaller league and thus, stronger talent pool -- would compile 454.1 WAR during the rest of their careers, along with a World Series title in 1957 and a pennant in 1958.

But there would be no such Astros championship for the 1990s Astros. The team of the future got disassembled too quickly.

Taking the pieces apart

With Biggio finally deciding to abandon catching after the 1991 season, Houston needed a backstop.

Rookie Scott Servais had promise, but the Astros didn’t see him as an everyday starter. Maybe he could be effective in a platoon role. Meanwhile, the emergence of Finley (.285 batting average, 8 HR, 54 RBI and 34 stolen bases in 1991, with a preference to play centerfield over a corner outfield spot) and Gonzalez (.254/13/69) gave the Astros confidence in its outfield.

So during the 1991 winter meetings, Houston traded Lofton to Cleveland in a deal that included left handed-hitting catching prospect Eddie Taubensee. Taubensee had a solid 11-year career — a dependable backstop with pop in his bat. But Lofton was a transcendent leadoff hitter, a spark plug on Cleveland’s pennant winning team in 1995 who would collect six All-Star selections, four Gold Glove awards, more than 2,400 hits, and 622 stolen bases during his 17-year career.

At least Houston got something of value in return for Lofton. The same can’t be said about another trade that happened near the end of 1992 spring training. Schilling, one of the team’s top relievers in 1991, was out of options — the Astros couldn't demote him. But he pitched poorly that spring (5.63 ERA) and Houston didn’t think it could justify keeping him on the roster, so Schilling was shipped to the Phillies for another underperforming pitcher, Jason Grimsley.

Grimsley never threw a pitch for Houston.

Then there was Schilling. The bullheaded military buff with the spiky hair and pierced ear, who’d recklessly speed down the expressway and pull the e-brake to scare and humor teammates, would figure things out in Philadelphia and become one of baseball’s best starting pitchers on his way to 216 career wins and more than 3,100 strikeouts. The bigger the stage, the better he was. His first season after his trade from the Astros, he pitched 10 complete games and four shutouts. By 1993 Schilling was pitching in the World Series for Philadelphia, carving up Toronto with a complete game shutout.

“It seemed like every time I violated one of my principles, it came back to bite me in the rear end. And that was definitely what happened with the Curt Schilling trade,” GM Bill Wood said. “If I could go back and turn that one back around and maybe Kenny Lofton, I think the rebuild would have happened a lot faster and the ballclub would have had even more success in the 1990s than they did.”

Like Lofton and Schilling, many of the emerging players on that 1991 team would find their greatest successes elsewhere: Caminiti and Finley in San Diego (and Finley with Arizona), Harnisch with the Reds, Gonzalez with Arizona, Kile for the Cardinals. All of those players besides Harnisch would become all-stars for other teams.

The only two of the players to stay in Houston, Biggio and Bagwell, led the Astros to the World Series in 2005 on their way to Cooperstown.

But thinking back to the 97-loss 1991 Astros, one can't help but wonder what those players might have accomplished if they had stayed together a little longer.