Remembering Rob Mallicoat

The former Houston Astros pitcher, who fought through injuries to spend three seasons in the big leagues, has died at age 60.

Rob Mallicoat kept battling.

He endured multiple shoulder surgeries to become a reliable bullpen arm for the Houston Astros in the early 1990s.

As Rob’s baseball career was ending, he sought a last-gasp opportunity as a replacement player with the Royals, then signed on with a team in Taiwan (he still owns the league record for the highest ERA), before walking away from baseball and launching a successful career in the tech industry.

And he spent the past half-decade completing round after round of treatment after being diagnosed with Stage IV colon cancer.

Rob died Sunday at the age of 60. He is survived by his three children, his mother, and the love of his life, his partner Tracy.

I had the honor of connecting with Rob while working on my book about his buddy and baseball teammate Ken Caminiti, and we kept in touch over the years. We had a number of deep conversations in the past few months. I’m proud to call him my friend.

Robbin Dale Mallicoat, Jr. was born on Nov. 16, 1964 in St. Helens, Oregon and spent his childhood in Oregon with his parents Dale and Jo and sister Marni.

Early in life, he was inspired by two passions: baseball and technology. Baseball was the initial pursuit. Technology would stay in the background for a little while.

Rob was a thin and gangly kid.

“I resembled a Q-tip with curly hair and black-rimmed glasses,” he told me.

This Q-tip could pitch. His junior year of high school with Hermiston, the lefty helped carry his team to the doorstep of the state championship game. He was pitching in the eighth inning against a tough West Linn team.

Batting was a pitcher and power hitter named Mitch Williams (yes, that Mitch Williams, “Wild Thing” himself). Rob made a good pitch and Mitch popped up the ball to the catcher, but the catcher couldn’t hang on.

Rob reared back and fired a fastball. Right down the pike.

Williams crushed the ball to dead center. Home run. Ballgame. The guy who’d become infamous for giving up the big one tagged Rob for the big one a decade earlier.

After the season, Rob’s parents moved to the Portland suburbs for work opportunities (T-shirts and marketing would give way for pizza shops and RV supplies), and Rob pitched his senior year for Hillsboro High School. Hillsboro wasn’t a great baseball school, but Rob still got noticed—scouts saw him pitch while tracking an opponent, Mitch Lyden of Beaverton.

The Detroit Tigers came calling and drafted him in the eighth round of the 1983 MLB Draft. The 199th pick. Roger Clemens and Mike Trout’s dad were also drafted that year.

Rob didn’t sign. His dad wanted him to go to college for at least a year, so he enrolled at Taft College, a junior college in California.

During his freshman year, pro scouts circled yet again, and the Houston Astros selected Rob in the Major League Baseball winter draft. This time, he ended up signing.

There was a lot of bouncing around in 1984—a theme that would play out in the decade ahead. College ball in California. Pro ball in New York and North Carolina. Instruction in Florida and Arizona. And then winter ball in Barranquilla, Colombia.

Have arm, will travel.

Rob’s 1985 season pitching for Osceola of the Single-A Florida State League was his breakout. He went 16-6 that year, with a miniscule 1.36 ERA and 158 strikeouts.

Some pitchers are pure power. Others, finesse. Rob was a cerebral pitcher. He thought deeply not just about pitch sequences, but the science and mechanics of pitching.

Which made him prone to overthinking on the mound. He’d throw a damn good slider—a swing-and-miss strike—and tell himself, “I can throw it better.” If he threw up and in, he wanted to throw it a little further up and in.

He’d try to throw the perfect pitch, even if the perfect pitch didn’t exist.

Heading into the 1986 season, Rob was among the top pitching prospects in the Astros system, and maybe in all of baseball. He got invited to MLB Spring Training and was being considered as the Astros’ fifth starter. Doc Gooden had made the jump from Single-A to the bigs, and maybe Rob could, too.

If only. During a washout day that spring in rainy Florida, Rob chose to go golfing. He was striding over a gully when he got his spikes caught in loose sand.

He came down, hit a soft spot on his heel, immediately winced in pain and dropped five or six F-bombs. Something was wrong. An X-ray didn’t show a break … but X-rays aren’t great at showing soft tissue damage. So it didn’t reveal that Rob had blown his Achilles tendon.

With the injury undiagnosed, Rob was still pitching, wearing heated plastic inserts molded to his ankle and wrapped with tape. But without any power and without the ability to follow through, since he couldn’t push off, he was overthrowing with his shoulder.

Everything that had gone right the season before went wrong in 1986. He started in Triple-A before backsliding, getting demoted to Double-A.

Rob couldn’t win. He went 0-8 with a 5.13 ERA before he got shut down for surgery.

If only. If Rob had stayed healthy and continued pitching at his previous level, he would have likely gotten called up in 1986 and could have helped contribute to the Astros’ division title.

He bounced back from injury in 1987 and starred once again, this time for Columbus of the Double-A Southern League—reinforcing the hot-cold pattern his career would follow.

Rob and his pal Caminiti were the league’s top vote-getters in all-star voting and he got the ball to start the all-star game, throwing two scoreless innings. A Sequoia-tall, imposing Expos prospect named Randy Johnson, The Big Unit, came on in relief.

Rob was 10-7 that year for Columbus, with a 2.89 ERA. Randy went 11-8 with a 3.73 ERA.

It’s easy to look back 30 or 40 years later and consider Randy’s plaque in Cooperstown and how he was the better pitcher in the long run. But at the time, in terms of their skills and their abilities to get batters out, Rob and Randy were pretty close.

The bounceback season earned Rob a callup to the majors. He made his Major League debut on Sept. 11, 1987 against the Padres. He entered the game in the bottom of the fifth with San Diego up 10-0.

The crowd was deafening—53,000 were in the stands. The Astros wanted a lefty, and Rob got the nod. The bullpen door opened, and he made the long, lonely jog from right field as the San Diego Chicken ran around, riling up the fans.

No pressure … just the pitcher and catcher, just as it always was.

The ball got tossed around the infield, and there stood Caminiti flipping his pal the ball. Ken didn’t have to say anything, just a glance was enough. Let’s get some outs, lefty.

Rob got some outs, alright. He pitched three innings, giving up one run and striking out two.

A few weeks later, he got the starting assignment against the Reds, managed by one of Rob’s childhood idols, Pete Rose.

“I was amped up. My parents flew down to see me pitch. And pretty soon, the bottom dropped out,” he told me.

He started the game by giving up three singles, but was able to work his way out of trouble with only one run in the first.

The second inning got ugly. Flyball. Walk. Walk. Groundout. Walk. Single. Single. Walk. Rob’s day was done. He got the hook after 1 ⅔ innings pitched.

He wanted to hit and go deeper in the game.

Afterward, his teammate Nolan Ryan pulled him aside. The Ryan Express told Rob how he’d gotten bombed in his first big league start, too.

Of course, Nolan had 772 career starts after that.

Rob never had another one.

If only. The following spring training, 1988, Rob was shut down due to lingering shoulder trouble, a byproduct of his changed mechanics from trying to pitch through his Achilles/ankle injury from two seasons earlier. But the procedure wasn’t effective, leading to a full shoulder rebuild. He missed the 1988 and 1989 seasons recovering and spent 1990 slumming around in the low levels of the minor leagues making sure he could still pitch.

By age 25, he’d gone from prospect to suspect. And he was trying to show the Astros that he could still contribute.

After 1,415 days of waiting, 1,415 days of self-doubt, 1,415 days of fear and determination and grit, Rob returned to the bigs in 1991.

His greatest day in baseball came on Aug. 18, 1991, a sun-kissed summer day at Chavez Ravine, when Rob threw three scoreless innings against the Dodgers to get the save.

He entered the game facing Los Angeles slugger Darryl Strawberry.

Three swings, three misses. He got Straw to flail at air.

Hall of Famer Eddie Murray followed with a skyscraping flyout that momentarily turned speedy outfielder Gerald Young into an air traffic controller tracking the ball into his glove.

After a single by Juan Samuel, Gary Carter—another eventual Hall of Famer—came up to bat. Carter came away empty. Whiff.

Mallicoat pitched the game’s final three innings for his only MLB save. After the last out was recorded, Rob got some kudos from his teammates and tapped his catcher Craig Biggio, yet another future Hall of Famer, on the shoulder as he walked around the field and soaked in the moment.

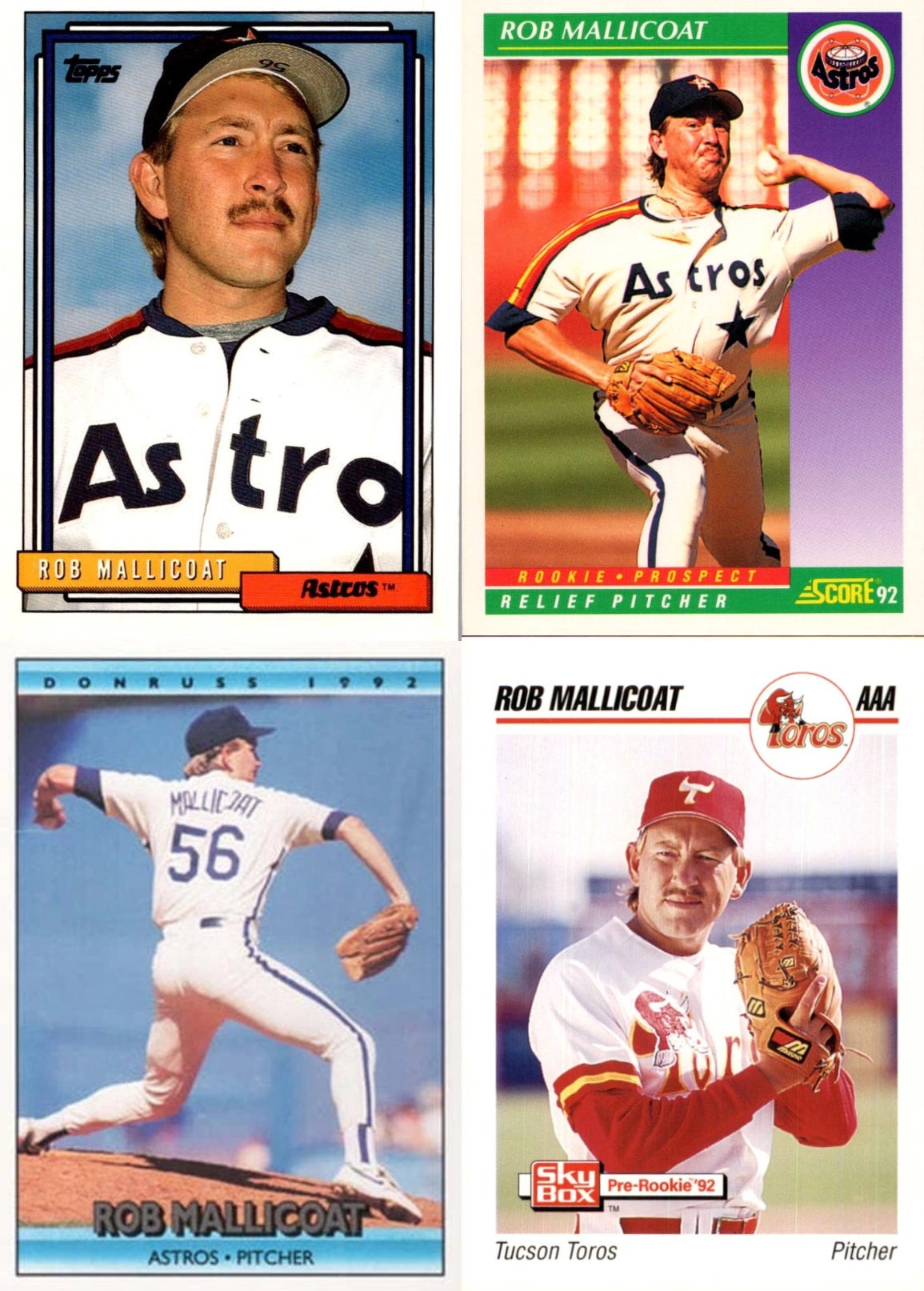

Rob shuttled back and forth between Triple-A and the bigs in 1991 and 1992 and stuck in Houston long enough to get a Topps card of his own, the ultimate sign of making it.

If only. Late in the 1992 season, the shoulder started acting up again.

“I was pitching against Fred McGriff in San Diego when I threw my fast sinker down and in and felt something crackle,” Rob told me. “It didn’t hurt, but it felt numb.” When you’re pitching, things shouldn’t feel numb or crackle. But it did after that pitch.

Rob continued throwing through the end of the season and rested that off-season, but when he returned for 1993, the shoulder was still acting up, meaning another surgery and another lost season.

Rob tried to hang on as long as he could. He pitched in the minor leagues in 1994 and appeared in big league camp the following year as a replacement player—with the Major Leaguers on strike, MLB rosters were temporarily filled by has-beens, never-weres, and also-rans.

And Rob.

Rob respected his former teammates’ stance. He was at the end of the line and knew he wouldn’t get another chance at the majors. He wasn’t taking anyone’s job. He hadn’t gotten rich from his pitching career, and with a family at home, he couldn’t turn down the paycheck.

During Rob’s time in big league camp in 1995, then traveling to Taiwan to briefly pitch for the China Times Eagles, he wrote blogs that got posted to Swarthmore College’s website, a “replacement diary.” You can still find his “replacement diary” online.

It was a blend of his two loves—baseball and computers—and reflected his transition from one career to the next. Rob’s final blog post was written on June 21, 1995. In that post, he was clear-eyed about his career.

“I have given it one more try three times... and have cheated the baseball gods out of a few more memories and I thank them,” he wrote.

He wrote at the time about his plans to “somehow get into the computer industry... my love of computers and fiddling around has become well-known with my team-mates.”

“I am writing this and beginning to feel the separation from something that has been an integral part of my life for over two decades. I can say I will miss the game, the guys, the fans, maybe the umpires ;), and the feeling of being a team and working for something. But the one thing I won’t miss is the pain my shoulder has given me the past years... But looking back it was not all that painful because I was doing something I really love!!!!”

A lot of those sentiments also apply to Rob’s long, difficult cancer battle and passing.

Rob definitely did get into the computer industry after his baseball career ended, working for companies like BMC Software, Quest and Microsoft.

Some former players are defined by their glory days and talk about them often; Rob was more circumspect. He wanted to establish himself with computers, and since throwing a baseball didn’t have much to do with computers, he didn’t tell his tech co-workers about his earlier career.

His worlds collided when his colleagues at BMC attended an Astros game and sat near the field level. Nolan Ryan sat two rows behind them. A work buddy turned to Rob.

“That’s Nolan Ryan behind us.”

Uh huh. Rob turned to Nolan.

“Oh, what’s up Nolan?”

“Hey Malli,” Nolan said.

The work friend was shocked. “You know him?”

“Yeah, we played ball together for a minute.”

“Excuse me. You played baseball with the Astros?”

“Yeah, dude.”

“Why didn’t you ever freaking tell me that?”

“Because I didn’t think it mattered. It wouldn’t come up in a conversation with a customer looking for some solution. How would I jump from talking about my pro baseball career?”

He got more comfortable talking about baseball, and reconnecting with colleagues from his prior life, through social media (he was also liable to get into dust-ups if he disagreed with someone).

And then there was Tracy, who Rob met in his fifties. They dated and got to know each other and went to concerts and dinner and walks. They played with the dogs and met each other’s kids, and everything was right.

But as things finally clicked into place with his love life, there was this other thing.

If only. When you rely on your body like Rob did as a pitcher, you become an expert on describing pain by joints and tendons and ligaments and body parts and playing through it.

Hip pain? Back pain? Scar tissue? Just pop Tylenol and grit it out, and all of a sudden, everything is better again.

He could tie every bump or bruise or twinge to a past surgery or injury and brush it off.

That was the case with his restless legs and sore hips. He found himself shifting around in his seat more frequently and getting a seat warmer to warm his legs. He thought he was just sore from playing tennis.

Turns out, it was colon cancer. Stage IV. It had spread to his liver and lung.

Rob endured years of treatment and various procedures. The chemo left him spent and suffering from nerve damage.

Still, he kept rearing back and throwing his best pitches. He wanted to stay in the game as long as he could.

Earlier this year, Rob had a meeting with his care team. They were checking his markers, which had shot up. The cancer was spreading, and treatment was becoming less and less effective.

He could have endured more treatment. But the chemo might have made him unable to walk. And all for maybe a few additional months at most.

Instead of additional treatment, Rob made a different choice.

“Right there, in the doctor’s office, my mind was made up. No more. I wanted to live. I wanted to go in my car and drive and enjoy my remaining days,” Rob told me.

That’s exactly what he did. He lived. He watched the sunrises and sunsets. Took that extra moment to enjoy the things and people around him.

He’d take a good, sturdy yellow Whiffle Ball bat and hit rocks and feel one with the universe.

I can’t help but laugh (cry? both?) at the fact that he died amid his hometown Seattle Mariners playing meaningful baseball for the first time in a quarter-century.

If only.

Timing was never Rob’s thing. But in the face of setbacks, Rob always found a way to make the most of his situation.

Even if Rob’s dreams didn’t quite play out the way he’d hoped, they still happened. He found true love. He made a career out of playing with computers. And for a few fleeting moments, he stood in the sunshine and threw smoke.

Thank you for your words about my friend Rob. He was one of a kind.