Ken Caminiti's steroids confession, 20 years later

Remembering the Sports Illustrated article that turned the baseball world upside down.

This text is adapted from my book Playing Through the Pain: Ken Caminiti and the Steroids Confession That Changed Baseball Forever.

Related coverage:

Ken Caminiti's steroids confession: baseball reflects

A CNN/SI producer and a motorcycle rally: The full story behind Ken Caminiti's steroids confession

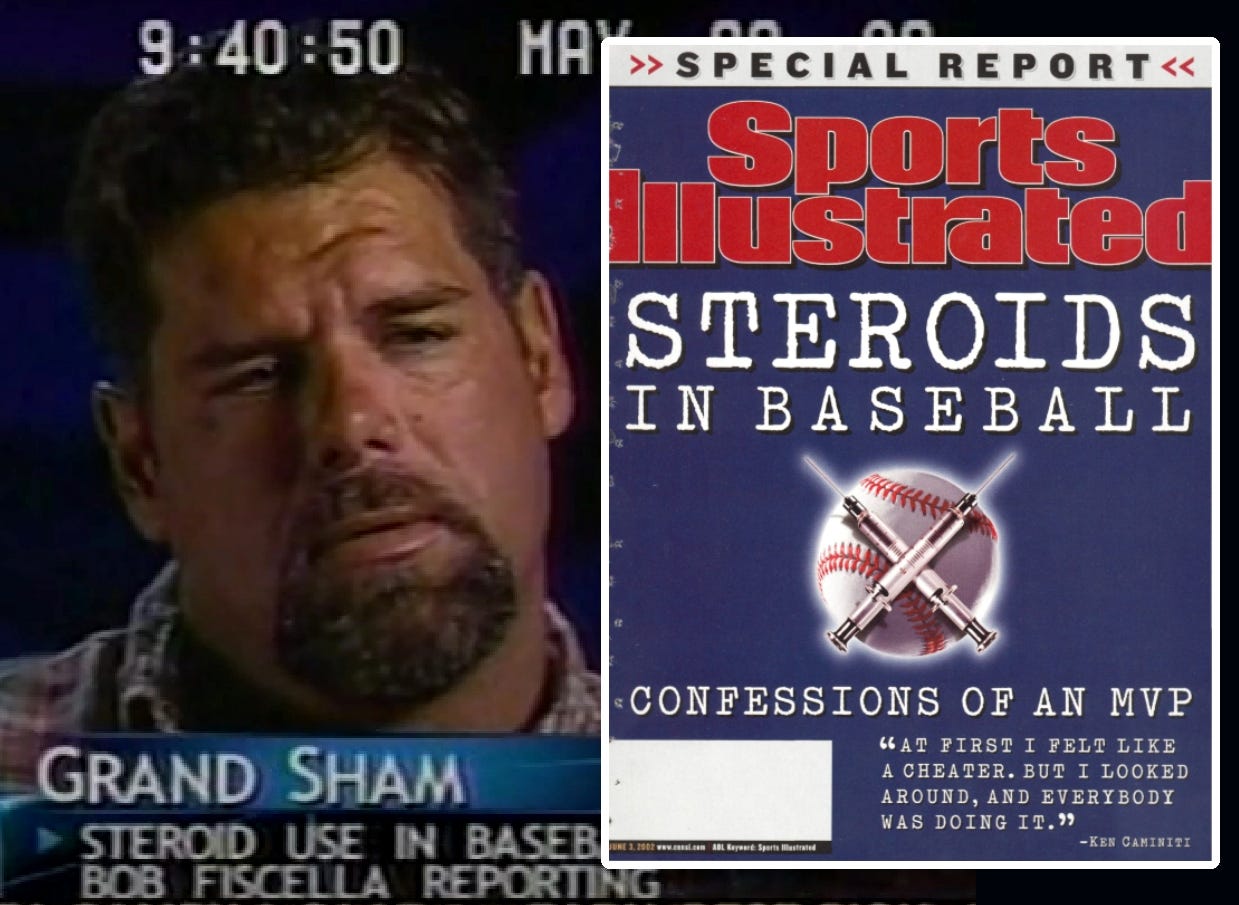

The Sports Illustrated cover featured two crossed syringes, forming an X atop a baseball, but it may as well have featured a live bomb with a burning wick.

>> SPECIAL REPORT <<

STEROIDS IN BASEBALL

CONFESSIONS OF AN MVP

“At first I felt like a cheater, but I looked around, and everybody was doing it.”

—Ken Caminiti

Twenty years ago today, on May 28, 2002, in tandem with the magazine issue hitting newsstands, CNN and SI launched a cross-platform publicity effort, pushing the story on TV and publishing coverage online. Caminiti’s quotes turned the baseball world upside down. The secret was out. Pandora’s box was open.

“I’ve made a ton of mistakes. I don’t think using steroids is one of them.”

“It’s no secret what’s going on in baseball. At least half the guys are using steroids. They talk about it. They joke about it with each other. The guys who want to protect themselves or their image by lying have that right. Me? I’m at the point in my career where I’ve done just about every bad thing you can do. I try to walk with my head up. I don’t have to hold my tongue. I don’t want to hurt teammates or friends. But I’ve got nothing to hide.”

“If a young player were to ask me what to do, I’m not going to tell him it’s bad. Look at all the money in the game: You have a chance to set your family up, to get your daughter into a better school. So I can’t say, ‘Don’t do it,’ not when the guy next to you is as big as a house and he’s going to take your job and make the money.”

“At first I felt like a cheater. But I looked around and everybody was doing it. Back then you had to go find it in Mexico or someplace. Now? It’s everywhere. It’s very easy to get.”

Tom Verducci’s article also contained quotes from pitchers Curt Schilling and Kenny Rogers, and outfielder Chad Curtis, who estimated that 40 to 50 percent of players used steroids—right in line with Ken’s estimate.

“Steroids can jump you a level or two,” Rogers told Verducci. “The average player can become a star, and the star player can become a superstar, and the superstar? Forget it. He can do things we’ve never seen before.”

Buy my book Playing Through the Pain: Ken Caminiti and the Steroids Confession That Changed Baseball Forever wherever books are sold. Signed copies are also available.

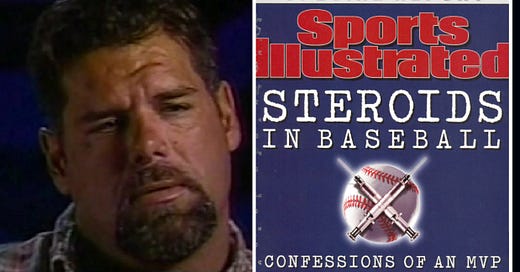

A video report by Bob Fiscella, a CNN sports anchor, included a mix of Caminiti’s on-camera quotes to CNN/SI producer Jules Roberson-Bailey and off-camera quotes to Verducci—a reflection of the team effort that contributed to the story coming together. Fiscella’s report led off CNN’s Wolf Blitzer Reports, ahead of stories about the death of congressional staffer Chandra Levy being labeled a homicide, the fight against the terror group al Qaeda in the Middle East, and President George W. Bush’s meeting with the pope to discuss the Catholic Church sexual abuse scandal.

Caminiti’s disclosure was bigger than sports. It was a national news story, a black eye for the national pastime.

Caminiti, as he was apt to do in interviews, told Verducci a handful of half-truths that ended up making it into the Sports Illustrated article—half-truths that would be upheld as fact in the ensuing decades. Ken said that he drove to Mexico himself to buy steroids, putting all the responsibility on his own shoulders (which was not, in fact, what happened).

Nor were the details of his PEDs regimen from his MVP season and the impact it had on his body. Some of the issues he faced would emerge later.

But what Ken told Verducci was close enough to the truth. And none of the hazy details changed the explosive fact that Ken was admitting, without remorse, that he had used PEDs.

Ken broke baseball’s omertà, sharing secrets from the clubhouse, and that was a cardinal sin. Not using steroids—that wasn’t the issue; it was talking about using steroids.

Reaction to Caminiti’s article was widespread and ranged from sympathy to scorn.

Some expressed concern for his well-being.

Some feigned ignorance.

Some criticized his motives.

Some argued that it undermined his accomplishments.

Some stated it didn’t surprise them.

Some agreed with him.

Some thanked him.

Some called for drug testing as a means of cleaning up the game.

Some called him a snitch.

Ken tried to defend or explain himself in subsequent interviews with Dan Patrick on ESPN Radio and on Jim Rome’s syndicated radio show. The crux of Ken’s issues came with that 50 percent figure. That’s what baseball players were griping the most about, since it implicated them.

“What’s really bothering me most about this whole thing is how it got blown out of context,” he told Patrick.

“I don’t know if I mentioned half or not. That is something that might have been thrown in my face or in my mouth. That’s not true. That’s a false statement. I didn’t mean half. There’s a couple of people that have done it that I know of. Baseball’s a pretty clean sport.”

Talking to Rome, his voice weary, Ken expressed frustration with the direction and tone of the article. “They came to me wanting to talk about life after baseball, and then it turned into this whole steroid thing,” he said. “I never knew the interview was going to go like that. It just got real ugly.”

Verducci said he was open with Ken about the story’s focus. While the journalist was interested in learning more about Ken’s life and recovery—topics that were both included in the article—“the story was about steroids,” Verducci said. Ken’s public backtracking reflected a desire to save face in the game.

He’d spent his career cultivating respect with fellow players, going all-out and playing the game the right way. It was painful getting attacked and called a rat or a snitch for talking about something that hundreds of people in the game, from teammates to opponents to fellow users, knew he was doing. Especially for someone like Ken, who’d spent his career trying to please others.

In private, Ken was proud of himself. He told the truth. His truth. This wasn’t about ratting out his fellow players or burning bridges. This was about Ken’s attempts to break free from his demons.

Ken comments—along with those of fellow slugger Jose Canseco, who promised to share his secrets in a book—forced Washington, D.C., to pay attention. Within weeks, the Senate held a subcommittee hearing on steroids in sports. “Like it or not, professional athletes serve as role models to our kids,” said Senator John McCain of Arizona, who requested the hearing.

The Major League Baseball Players Association had held firm that drug testing was a violation of players’ privacy. But with Congress threatening to hold baseball accountable, and with a cloud hanging over the game, and amid tense talks to sign a new collective bargaining agreement and avoid a strike, the players association agreed to allow blind testing of players for 2003—the testing would expand if more than 5 percent of players tested positive.

But that would never happen, right?!