Hall of hypocrisy

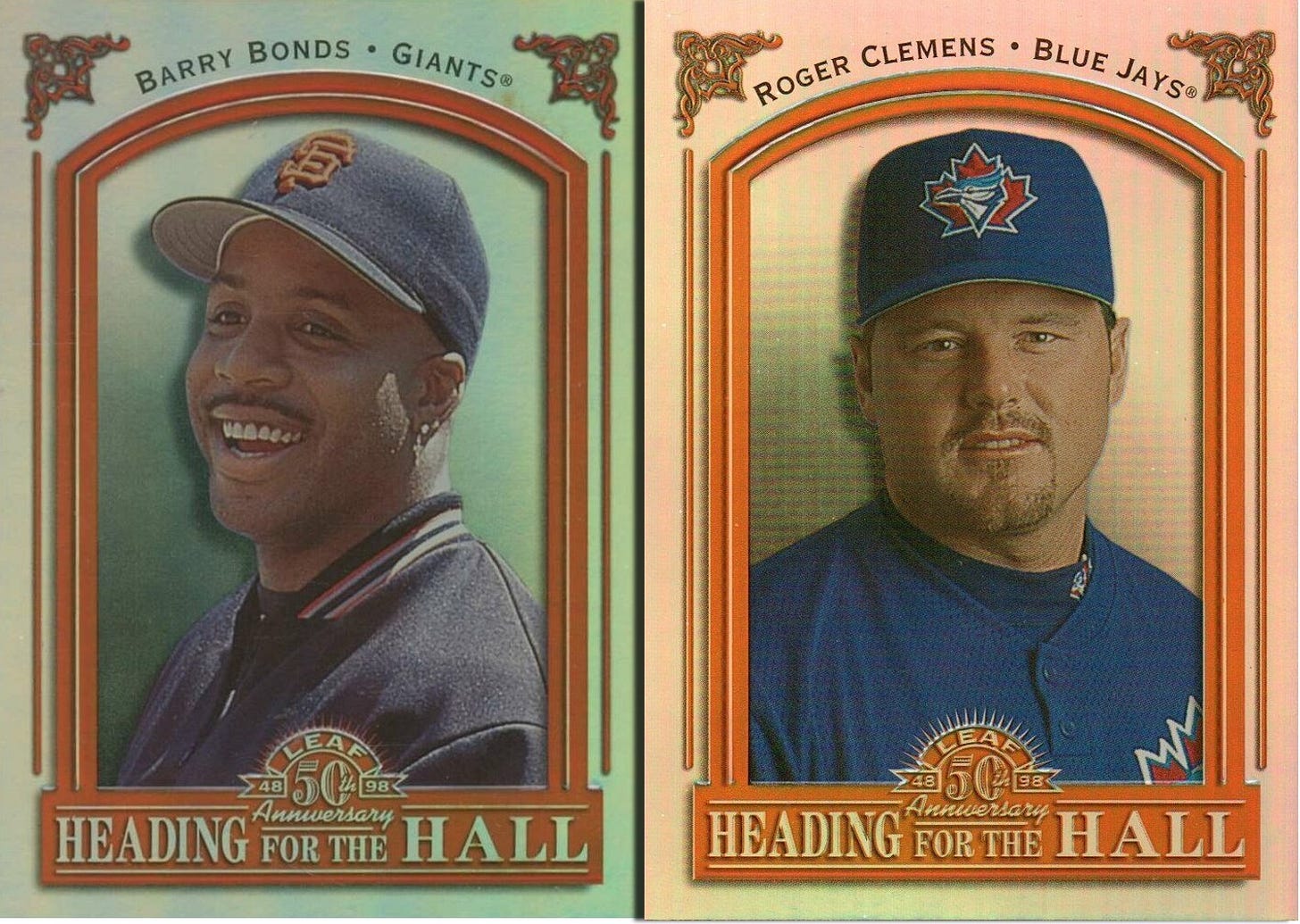

Barry Bonds and Roger Clemens are on the Hall of Fame ballot for the final time. There aren't any valid reasons anymore why they shouldn't get elected.

Who belongs? Who doesn't? Who knows?

As the calendar approaches January, the annual conversation about baseball's next Hall of Fame class has commenced. This year's vote is especially meaningful because of two players on the ballot for the final time, Barry Bonds and Roger Clemens.

Both players have extremely compelling Hall of Fame arguments.

Bonds: A record 762 home runs and 2,558 walks ... .298 batting average ... 2,935 hits, 601 doubles, 1,996 runs batted in, 514 stolen bases ... seven MVP awards ... eight gold gloves, 14-time All-Star

Clemens: 354-184 record ... 3.12 ERA, 4,672 strikeouts ... 143 ERA+ ... seven Cy Young awards, one MVP award, 11-time All-Star ... two-time World Series champ

But they’ve languished on the ballot, year after year, because they’re both linked to steroids and are temperamental, loathsome people.

The Baseball Writers’ Association of America, whose members are tasked with voting on each Hall of Fame class, has never defined parameters on how to handle known or suspected PED users. I spoke to sportswriter Rick Telander about voters' confusion some years ago.

"I wanted to hold a mirror up to Major League Baseball, to the writers in particular. I mean, we have to make decisions. Is Andy Pettitte — OK, he used — can we vote for him because he’s a good guy? Do we not vote for Bonds and Clemens because they’re such jerks, and because their numbers were just so crazy? I don’t like having that responsibility, but I really believe in the Hall of Fame and I believe in people being rewarded for greatness,” Telander said.

The problem with the ongoing conversation around steroids is that it fails to account for the pervasive nature of PEDs within the game during the 1990s and early 2000s. These players are being judged individually in a vacuum, did-they-or-didn't-they, when baseball’s steroids cloud was cultural and institutional in nature. The problem wasn’t who did or didn’t use steroids, but that every player had to make their own choice.

As Tom Verducci, whose 2002 Sports Illustrated article about Ken Caminiti's use of steroids blew the lid off the scandal, told me, "Besides seeing bodies change, I had more clean players coming up to me complaining that things had become unfair, and I heard this from multiple players that they felt like they either had to compromise their integrity, which they didn't want to do, compromise their own health -- because at the time there were still a lot of concerns about the effects of using steroids -- or play at a disadvantage."

Bonds' or Clemens' decision whether or not to use steroids was the same one that every player -- the injured middle reliever, the scrub fourth outfielder, the journeyman trying to stick on a big league roster, or their fellow superstars -- had to consider. Many players from baseball's Steroids Era are already enshrined. Barry Larkin. Roberto Alomar. Larry Walker. Ivan Rodriguez. Mike Piazza. Cal Ripken, Jr. Rickey Henderson. Jim Thome. Pedro Martinez. Jeff Bagwell. Craig Biggio. Edgar Martinez. Ken Griffey, Jr. Frank Thomas.

Some of those players have faced their own whispers of PED use. Some haven't. But they all could have used. They all had to consider it. And they played alongside or against other players who were juicing.

It would be great if all of our baseball heroes weren't tempted to try PEDs ... but even the greats are fallible, as Hank Aaron was when he was slumping in 1968.

“I was so frustrated that at one point I tried using a pep pill—a greenie—that one of my teammates gave me,” Aaron wrote in his autobiography, I Had a Hammer. “When that thing took hold, I thought I was having a heart attack. It was a stupid thing to do, and besides that, I shouldn’t have been so concerned about my hitting in the first place."

It’s difficult to recognize your talent slipping, to know you aren’t the player you used to be, to see others bypassing you because of the things they are putting into their bodies. Steroids, for some players, helped to counteract the aging process and to pause Father Time. The chance to hang on a little bit longer. The opportunity to be your best, and in a select few cases, to become immortal.

And if the game wasn’t testing back then …

Clause 5 of the BBWAA's rules for election outlines the qualities that voters should consider for candidates: Voting shall be based upon the player's record, playing ability, integrity, sportsmanship, character, and contributions to the team(s) on which the player played.

Integrity and character. The hall is full of figures who fall short of those lofty and vague ideals. Rogers Hornsby was hated by teammates and constantly bet on horses. Cap Anson was a virulent racist who helped to deepen segregation in the game. Pud Galvin received injections containing monkey testosterone. Gaylord Perry illegally doctored his pitches.

It also seems hypocritical that while Bonds and Clemens continue to be vilified, former commissioner Bud Selig, the man whose sloth-like response to steroids in the game allowed the problem to proliferate, waltzed into the Hall without as much as a sideways glance, gaining entry through a trapdoor called the Today’s Game Era Committee.

The reality remains: before or after steroids, Barry Lamar Bonds was the scariest hitter in baseball. He was brash and bold, flashy and outspoken. He was so good. Who else gets walked with the bases loaded? His strike zone was about the size of a thimble because his eye was so sharp. You can still envision him ticking and tocking his bat ahead of the pitch, rotating his hips, turning on the ball, and smashing it into McCovey Cove.

Splashdown.

The BBWAA writers are stuck with an unenviable task, serving as the moral arbiters of a hall of hypocrisy. There are already scoundrels in the Hall of Fame, and suspected steroids users, as well as lesser players whose careers overlapped with Bonds and Clemens.

The Hall of Fame has been aiming for years to punish players from the Steroids Era, case in point the board of directors' 2014 decision to reduce players' candidacy from 15 years to 10 without expanding the voting cap, which remains at 10 players. Then-Hall president Jeff Idelson suggested the changes were all about "relevance."

But I'm not really sure how much relevance an institution could have when it enshrines Chick Hafey (a left fielder who was about as valuable for his career as Ron Gant) and Jesse Haines (a starter whose stats are comparable to Mike Hampton's) but fails to honor the actual best of the best.

This year's vote is especially relevant because of two additions to the ballot, Alex Rodriguez and David Ortiz, who are both reported to have failed blind drug tests in 2003.

Rodriguez -- who MLB willfully allowed to use PEDs with an exemption, and later got suspended in the Biogenesis scandal -- has amazing career stats (his 696 home runs are fourth all-time behind Bonds, Aaron and Ruth) but lots of baggage.

And then there's Big Papi, a likable guy who will forever be beloved in Boston for winning three championships for the Red Sox. Ortiz slugged 541 career home runs, good for 17th all-time, but he also spent most of his career as a designated hitter.

Ortiz's career wins above replacement is 55.3. Bond's career WAR, meanwhile, is 162.7 -- almost three times that of Big Papi.

Where Ortiz has the stats to enter Cooperstown, Bonds has the stats of an inner circle Hall of Famer.

Given the PED cloud hanging over both of the players, it doesn't seem fair that Ortiz, even with his championships, could get in before Bonds. Unless friendliness is worth a surprise 110 Wins Above Replacement. And if it is, then Sean Casey and Curtis Granderson are hall of famers, too.